A recent trip to Kirkenes and the surroundings was really revealing in many ways. Of course for someone who has worked most of the professional life as an anthropologist in the Russian Arctic, I was curious to find out how the border with Russia that is now less permeable influences life on the Norwegian side. Our colleagues at the Barents Institute in Kirkenes, who were very kind hosts, study this process of course right in front of their door, so they say one can become even saturated with this over time. How much more can you study this when you see it, live with it, are part of it every day? And yet, of course they continue monitoring these developments, but also venture in to other topics.

One of these topics that we might jointly work on is the Finnish speaking population in East Finnmark, or those with Finnish ancestry. I find out from Bjarge Fors and Anne Fiegenschou that by far not all of them would like to be called Kven. There seems to be a difference between Norske Finner (Norwegian Finns) and Kven. At first glance it seems that those people associate themselves with Kven who do not want to be considered really Norwegian, nor Finnish. But what is it that people build their distinction on? A particular livelihood, animals, some special skills? Bjarge thinks that Kven people took up some niches that were left unoccupied by either Norwegians or Sámi in the area. For example smith, or artisans. What is left of that nowadays? For that question of course they say one has to go to Pikkusuomi, the village of Bugøynes (Pykeija), where Elsa Haldorsen promotes their own brand of livelihood by Finns an the shore of the Arctic Ocean. Anna Stammler-Gossmann has been writing on this from our team. But there is more to this than Bugøynes (Pykeija), as I find out. Even in Kirkenes I met on my second day someone who just started chatting to me because of the Finnish number plate on my car. He speaks Finnish in a funny way, approximately as fluent as I (which means in fact not quite fluent:). His ancestors are from Finland but already for generations have lived in Finnmark. Proudly he presents his Norwegian ID card to me: Laurila is the surname. I thought “wow, that is quite impressive how just a Finnish number plate wakes up immediately that Finnish feeling”. And he does not call himself Kven, but Norske Finner.

Later I find out from a photo exhibition that around 1900 the majority of people in the municipality of Kirkenes were considered Finnish. According to a masters thesis that I found 43% ( and 36% Sami and 21% Norwegians, Skirmante 2020:2, citing Lund, 2015). That would change of course rapidly when industry started taking off, with the opening of the Björnevatn mine, and later with the German occupation during WWII. I also had no idea that Kirkenes was one of the cities most fiercely fought for in the entire war. More than 300 bomb attacks on this small town! For years people would run to a bomb shelter for civilians almost like a daily routine. Sounded like a miracle that less than a dozen civilians died from these more than 300 bombings during the entire war! What an organisation, in a city where hardly any house was left intact at the end of the war!

Close to the bomb shelter is the monument celebrating the liberation of Kirkenes from the Nazis by the Red Army. No surprise people were happy back then when their town was finally liberated. But I was impressed to see that they keep this monument in so good shape now too. Look at the neatly arranged decoration at the bottom in the colours of the Russian flag!

This seems to me remarkable even more so now with the recent political situation of conflict between Russia and NATO countries (of which Norway is one of course). And given that the Russian border is just half an hour drive from that monument.

This brings us back to the present too: the border is anything but closed: there is daily official bus transportation going between Murmansk and Kirkenes, and according to a traveller, who crossed the border last week, the crossing goes smoothly. Nobody asks questions on either the Norwegian or the Russian side as long as you have the necessary visa and passport. The cooperation also seems ongoing on the marine side: at the “Kimek” wharf in Kirkenes I see that vessel under Russian flag with cyrillic letters called “Saami” (see picture above). Wow, doesn’t that epitomise the contemporary expression of borderland mingling? And in the shops I hear quite some Russian speech, not only because around 400 of the around 4000 inhabitants of Kirkenes are Russian. Also because Russian sailors are still there, maybe from that “Saami” vessel? Now I understand, this is the everyday life with the border that the colleagues from the Barents Institute were talking about.

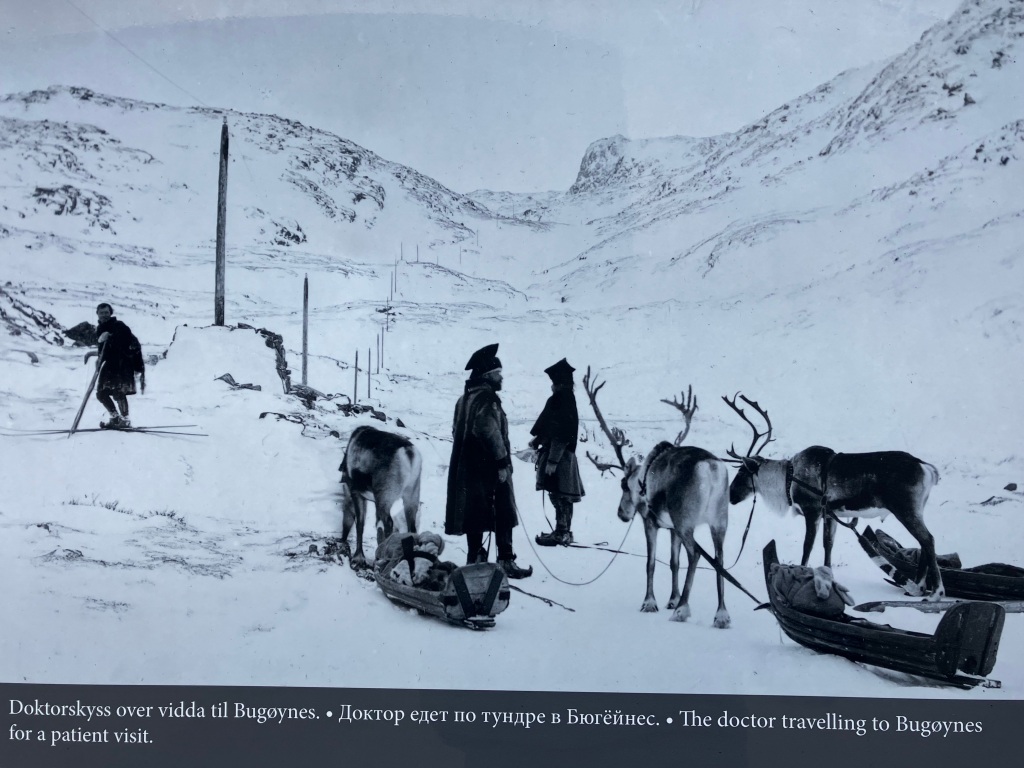

When Kirkenes was only a couple of wooden houses, before the mine opened, obviously travelling was much harder. The nice photo exhibit on the main square in Kirkenes has some nice images about that: the doctor in the early 20th century used reindeer as a regular transport to get to the neighbouring settlements, as on the picture above on his way to Bugøynes .

These pictures I found quite interesting in terms of reindeer herding: I had not heard before of this special “moss dryer” that is on this picture. Did they dry lichen? Did they feed reindeer already in the early 20th century? Were the pastures already back then scarce? So this whole carrying capacity problem of pastures, and the icing over isn’t that new after all… Also note the two different kind of sledges on the picture. On the left side there is the one with the runners, behind the reindeer, whereas the pulkka type is between the woman and the reindeer. So they were using different sledges at the same time? Lots of more question to explore if we start working with people there. Hopefully soon!