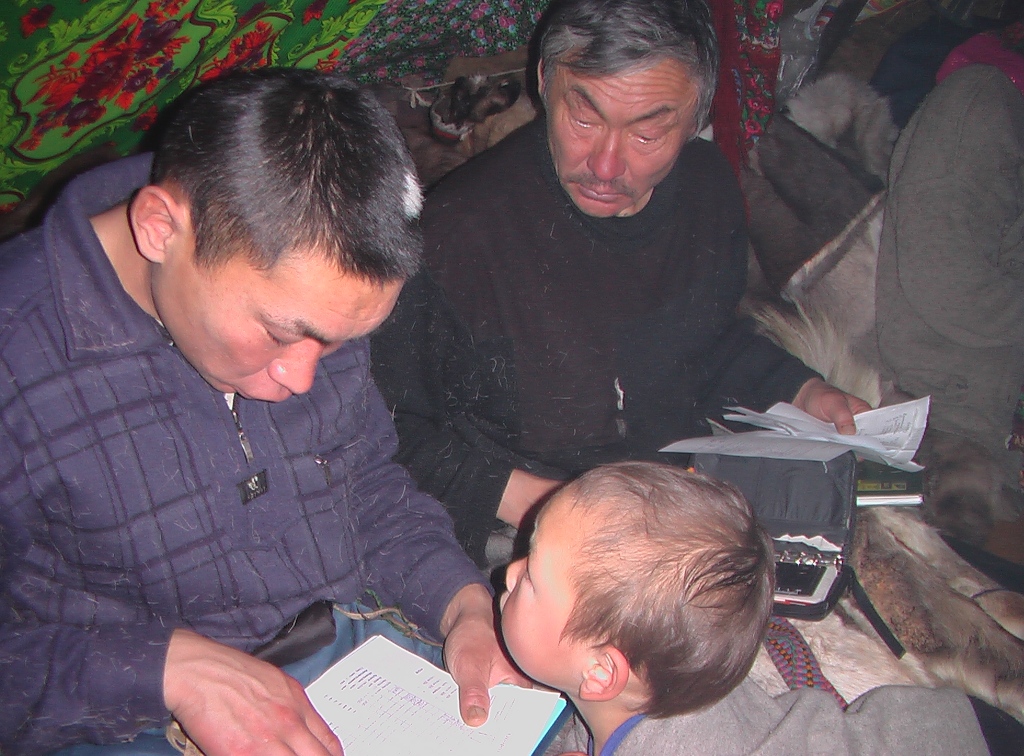

The news from the tundra was a shock: last year we celebrated Sergei Serotetto’s 66th birthday together in his chum in the tundra of Yamal. Full of his typical humour and warmheartedness, surrounded by his family of three generations. Now he passed away, on the 27th May, in the tundra. Sergei Serotetto was one of the best-known reindeer herders in the Soviet Union, in post-Soviet Russia, as well as in the rest of the world probably.

He was among the very few nomads who were invited to the Soviet Union to the Union-wide congress of the communist party of the Soviet Union, which happened only once in five years – and he declined!!! He told the party leadership that he is too busy herding reindeer! He was among the first herders who got international visitors, on field expeditions by the Smithsonian institution for example, in the 1990s, with Bill Fitzhugh, Igor Krupnik, Andrey Golovnev, Sven Haakenson, Natalya Fedorova, Konstantin Ochepkov and others. After the Soviet Union he also became well-known abroad, through numerous photos by Bryan Alexander. He was of course also at the founding congress of the World Reindeer Rerders Association in Nadym in 1998, and in his active position in the association travelled to most other reindeer herding places of the Eurasian Arctic, including Rovaniemi and Jokkmokk, where there were also congresses later.

But ar beyond reindeer herding experts, Sergei became also a TV star:) an Irish and National Geographic documentary production with him as a principal character won the “Spirit of the Festival Award Winner Celtic Film Festival 2003″. Three years later I chose him and his family as the most reliable and impressive ambassadors of a passionate nomadic way of life, for the BBC/discovery series “Tribe”. I was told this programme was watched by over forty million people worldwide. More intellectually, Sergei co-shaped the careers and research of many scholars on the Yamal Peninsula, and has thus had a significant influence on studies of nomadic pastoralism, Arctic studies, indigenous studies and Arctic Anthropology of course. I am pretty sure the dissertations by Andrei Golovnev, Sven Haakenson, myself, Ellen Inga Turi, Roza Laptander, and surely many more would not have been as rich without the input of Sergei and his family. He was a great supporter of our research, practically by hosting many of us, and theoretically through rich and intense conversations, and through sharing his wisdeom with us through his narratives that make Nenets culture better understandable also for non-Nenets. Many of us in the scholarly world feel indebted to him.

I guess his principal motivation for this openness to outsiders was his curiosity for the world, his intellectual hunger to find out about all sorts of different environments and people, in combination with his warmhearted character and a never-ending hospitality. Secondly, he thought that positive publicity for their way of life would indirectly help make the case for Nenets reindeer nomadism during intensive industrial development. As a true professional, however, he always maintained that everybody should to their job that they can do best – so he would not want to become co-author on publications even when invited. He said “you can do that writing best, and I am good at reindeer herding”. Maybe this was the way for him to preserve his respected status in the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia as well as influencing the public image of reindeer herding .

Sergei lost his father early on and was brought up in difficult times in the 1950s by his single mother. Later on his predessessor in the 8th Yar Sale brigade, from the respected Khudi clan, became his teacher. Sergei told it was thanks to his wisdom that he got both the skills and the enthusiasm for the nomadic way of life. He also emphasized that part of that education by his teacher was the pressure to get formal education too, for which Sergei has a very high appreciation. “He just told me ‘you have to go to town and study, and he set it all up and sent me away’, and I did study”. He was convinced that this combination of tundra skills acquired by lived experience jointly with a wise elder, and formal education in town was the right mix that is needed to lead a successful nomadic way of life.

This is also the approach that Sergei continued with his own children and grandchildren. In his large extended family, all children are well educated, his son Lev as a veterinarian, who inherited the big reindeer herd and camp. His numerous grandchildren continue that path. Those who had the honour to be long-term guests of Sergei’s in the tundra will confirm that in this family you never think that the nomadic life in the tundra will cease. Sergei has taught his whole extended family how to weather almost any adverse effects skilfully, be it iced-pastures, industrialisation, political change, reindeer disease, or social pressure. One could say he was a the epitomy of Nenets nomadic resilience that several of us have been writing about.

In this way, Sergei has also made a big contribution to deconstructing the image of the poor marginalised vulnerable indigenous victims of bad external pressures. Staying with him, herding reindeer with him, joining him on the migration, and listening to his narrative made us not only understand, but also feel that there is a very different story to tell. One of enthusiasm, passion, love for this way of life, incredible toughness, stamina and wisdom to change the things that you can, and accept those that you can’t (and distinguish one from the other).

Sergei is going to be buried in the Yamal tundra at their clan-cemetery. His departure is a big loss for Nenets reindeer nomadism, for the scholarly community interested in Yamal, for numerous people whom he influenced thoroughly, but first and foremost for his extended family. Warmest condolences to them! May Sergei’s energy and spirit live on through them in continuing his legacy.

Кочевое оленеводство как профессия, образ жизни, страсть и любовь: Сергей Серотетто

Известие из тундры стало шоком: в прошлом году мы вместе отметили 66-летие Сергея Сэротэтто в его чуме в тундре Ямала. Полным его типичного юмором и сердечности, в окружении своей семьи из трех поколений. Теперь он ушёл с жизни 27 мая в тундре. Сергей Сэротэтто был одним из самых известных оленеводов в Советском Союзе, в постсоветской России, а также, вероятно, в остальном мире.

Он был среди очень немногих кочевников, которые были приглашены в на всесоюзный съезд Коммунистической партии Советского Союза, который проводился только раз в пять лет – и он отказался !!! Он сказал партийному руководству, что слишком занят оленеводством! Он был одним из первых оленеводов, которые принимали иностранных гостей, например, в полевых экспедициях Смитсоновского института в 1990-х годах, вместе с Биллом Фитцхью, Игорем Крупником, Андреем Головневым, Наталья Фёдоровой, Константином Ошепковым, Свеном Хакенсоном и другими. После Советского Союза Сергей Соокович стал известен и за рубежом благодаря многочисленным фотографиям Брайана Александера. Он, конечно, также присутствовал на учредительном конгрессе Ассоциации оленеводов мира в Надыме в 1998 году, и, занимая активную позицию в ассоциации, ездил в другие оленеводческие места евразийской Арктики, включая Рованиеми и Йоккмокк, где также проходили Конгрессы. Но Сергей был не только экспертом в области оленеводства, но и телезвездой 🙂

Документальный фильм ирландского телевидения и National Geographic с ним как главным Ненецким героем (с братом Алексанр вместе) получил премию «Дух фестиваля» Кельтский кинофестиваль 2003 года. Три года спустя я выбрал его и его семью как самых надежных и впечатляющих послов страстного образа жизни кочевников для сериала BBC / Discovery. Мне сказали, что эту программу посмотрели более сорока миллионов человек по всему миру. В интеллектуальном плане Сергей сушественный вклад делал в карьеру и исследования многих ученых на полуострове Ямал и, таким образом, оказал значительное влияние на изучение кочевого оленеводства, арктических исследований, исследований коренных народов и, конечно же, арктической антропологии. Я почти уверен, что диссертации Головнёва, Хакансона, моя собственная, Эллен Инга Тури, Розы Лаптандер и многие другие не были бы такими же богатыми без участия Сергея и его семьи. Он был большим сторонником наших исследований, на практике принимая многих из нас, а теоретически участвуя посредством насыщенных и интенсивных бесед, а также делясь с нами своей мудростью через свои рассказы, которые делают ненецкую культуру более понятной и для внешнего мира. Многие из нас в научном мире чувствуют глубокую благодарность перед ним. Я предполагаю, что его основной мотивацией для этой открытости для посторонних было его любопытство к миру, его интеллектуальный голод, чтобы узнать о самых разных средах и людях, в сочетании с его сердечным характером и нескончаемым гостеприимством. Во-вторых, он наверное думал, что позитивная реклама их образа жизни косвенно поможет поддерживать кочевничество ненцев в период интенсивного промышленного развития. Как настоящий профессионалы, Сергей утверждал, что каждый должен делать то, что он умеет делать лучше всего, поэтому он не хотел становиться соавторами публикаций, даже если его и приглашали. Он сказал: «Ты лучше умеешь писать, а я умею оленей пасти». Возможно, это был способ для него сохранить свой статус уважение в советском Союзе и постсоветской России, а также повлиять положительный на общественный имидж оленеводства через науку и телевидению.

Сергей рано потерял отца, и его мать-одиночка воспитывала его в трудные времена 1950-х годов. Позже его предшественник в 8-й бригаде Яр Сале из уважаемого клана Худи стал его учителем. Сергей сказал, что именно благодаря его мудрости он приобрел навыки и энтузиазм в отношении кочевого образа жизни. Он также подчеркнул, что частью этого обучения его учителя было также настаивание на получение формального образования, что Сергей очень ценил. «Он просто сказал мне, что тебе нужно поехать в город и учиться, и он все устроил и отослал меня», и я действительно учился ». Он был убежден, что это сочетание навыков тундры, приобретенных жизненным опытом вместе с мудростей старейшиной, и формальным образованием в городе было правильным сочетанием, необходимым для ведения успешного кочевого образа жизни. Такой же подход Сергей продолжил со своими детьми и внуками. В его большой семье все дети хорошо образованы, его сын Лев – ветеринар, унаследовавший существенное стадо оленей и стойбище. Многочисленные внуки Сергея продолжают этот путь. Те, кто имел честь быть постоянными гостями Сергея в тундре, подтвердят, что в этой семье никогда не подумаешь, что кочевой образ жизни в тундре прекратится. Сергей научил всю свою большую семью умело выдерживать практически любые неблагоприятные воздействия, будь то обледенение пастбищ, промышленное освоение, политические изменения, болезни северных оленей или социальное давление. Можно сказать, что он был воплощением стойкости, о которой писали некоторые из нас.

Таким образом, Сергей также внес большой вклад в деконструкцию образа бедных, маргинализированных уязвимых коренных народов, жертв плохого внешнего давления. Живя с ним, пася с ним оленей, присоединяясь к нему в каслании и слушая его рассказ, можно было не только понять, но и почувствовать, что есть совсем другая история: история кочевничество как энтузиазма, страсти, любви к этому образу жизни, невероятной стойкости, выносливости и мудрости, позволяющих изменить возможное, и принять как дано то, что не возможно менять (и отличить одно от другого).

Сергея похоронят в ямальской тундре на их Родовом кладбище. Его уход – большая потеря для ненецкого оленеводства, для научного сообщества, интересующегося Ямалом, для многочисленных людей, на которых он оказал огромное влияние, но в первую очередь для его большой семьи. Искренние соболезнования им! Пусть энергия и дух Сергея живут через них в продолжении его дела.

Very interesting. I travel the Sami region of Sapmi frequently and was amazed by the info you offered in this article.

Thank you, Florian, for this text.

I will remember Sergei Sookovich. He was that person who always supported us, and me as well. I remember how he was proud when I came to the tundra with the BBC team as an interpreter. He said, yes! Look, we, the Nenets, can also translate from English. That was a big compliment. Also in 2006 once he said: “Our planet is round, and it does not matter where is any ecological catastrophe, its results will go around the whole Earth. The same is with climate change or any positions, and we all have to live with this”.

That time I came to the tundra without any proper female clothes. His wife, Galina lent me a new female fur coat yagusha and a nice reindeer fur hat. After Sergei told me one story that once a long time ago his father travelled to the Ural Mountains to the sacred place. There was an old man, maybe my grandfather who helped him with shelter and food. Therefore, in this way, his family would like to thanks him for this. For me, it was a good excuse and I felt also proud for my grandfather, even maybe it was another person. But by this way, Sergei comforted me. I am also thankful to him for this.

May his soul rest in peace.

Thank you for sharing this story Roza, with your grandfather. What an amazing example of the reciprocity of gratitude in the tundra. Over three generations!

Thanks Florian, for this news, which is indeed sad but also important for the wide world to know. For all of us who knew Sergei, we sincerely appreciate your heartfelt words. I am among the fortunate people to have known Sergei for many years and to have migrated with his family. It was always a supreme pleasure and to be around him in any context, and especially with his family.

I believe the first time i met Sergei was with you at the reindeer herders’ congress in Yakutsk ca. 2005. It was, I think, february and so cold my flight from Moscow Sheremetyovo was detoured to Mirnyi because of the “ice fog”. But when i finally arrived at the reindeer congress we chatted outdoors with Sergei at the herders’ market “na ulitsa” in ca. -44°C air temps. Amidst the biting cold, Sergei was like a warm presence. He emanated vitality and – as i came to know later – infinite wisdom.

You are extremely fortunate to have had such a mentor as Sergei. And you will certainly maintain close ties with his family for a long time to come, as he would have wanted. Your many shared memories will help sustain you. If you decide to create a repository for photos of him, please let me know and I will be happy to comb my archives to provide images which his family may well appreciate.