This was one of the questions covered in an interdisciplinary exhibition on the effects of global warming and melting permafrost in Yakutia, on display in the Hokkaido museum of northern peoples. The exhibition with the title Thawing Earth – Global Warming in Central Yakutia is a nice example of co-production of knowledge between natural and social scientists and outreach experts, in a Japanese research project entitled “Arctic Challenge for Sustainability (ArCS)”. Organisers Atsushi Nakada from the Hokkaido Museum and Hiroki Takakura from the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies in Japan connected the available science evidence on climate change in Central Yakutia with practitioners’ knowledge on the effects. For a western visitor to the

exhibition it was also interesting to observe how Japanese colleagues present this problem to their own audience in one of Japan’s northernmost cities – Abashiri.

The exhibition stands out with its exceptionally well written introductory texts about the climate, the people, the livelihoods in Yakutia. In text boxes not more than 100 words each, Nakada and Takakura managed to bring the basics to the audience: that global warming has local impacts on local people – in Siberia as in Japan. They draw the connection between the natural environment and local livelihood like this:

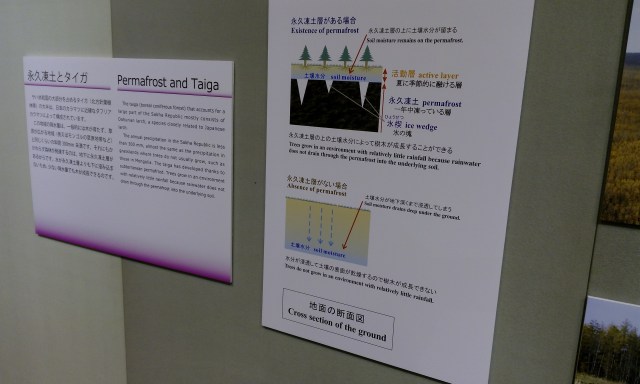

The Taiga (not the treeless tundra) developed in Yakutia thanks to permafrost.

Permafrost does not allow the water to drain into the ground. Otherwise, the area with a precipitation as low as 300 mm annually would not have been able to sustain such forests. In the absence of permafrost, this area would just have been grassland like in Mongolia.

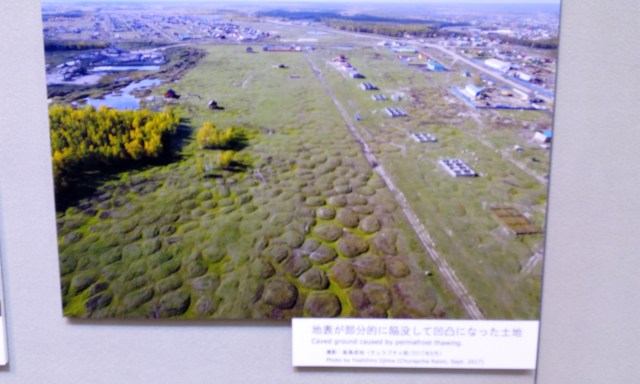

The Sakha developed a complex animal-based livelihood in this ecosystem, culturally significant linked to horses, cattle and reindeer. The former two particularly benefit from grazing on a permafrost-related habitat-formation: thermokarst, called Alaas. These form when the permafrost melts and water drains down to greater depths. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles also let the ground bump up, making grassland much harder to use for the animal herders. The natural phenomena behind this and the consequences for people are explained in the best accessible language. On these connections there is also a good article from Crate et al (2017).

Nakada and Takakura together with their colleagues concluded that the numbers of cattle in Yakutia has already decreased among other reasons because of less grassland available due to melting permafrost and changes in thermokarst landscapes. They asked Aytalina Ivanova from Yakutsk, an ArcArk collaborator, to comment on this and other conclusions, and she emphasized that the causality is complicated.

There are many reasons why the number of cattle decreases, one of which is the prestige of horses in Sakha society and religion. This aspect is especially well displayed in the exhibition as well. The market for horse meat is stable, and rearing horses is less work than cattle. Therefore horse herding is more stable than cattle breeding.

Together with other colleagues from Yakutia, the organisers also conducted a survey using a questionnaire in villages, where residents commented with multiple-choice questions on the effects of environmental changes. They found that around half of the respondents noted more precipitation, while the other half noted less precipitation as environmental change. Probably this can be explained by different respondents focusing on different seasons: maybe some people noted less snow, while others noted more rain.

As anthropologists believing in long-term fieldwork results from multiple-choice questionnaires conducted in village schools make us very cautious to believe the results. But in-depth qualitative findings from fieldwork on animal-herders traditional knowledge of a changing environment is harder to display in a 100 words text box or in one diagramme, as used in this exhibition.

At the end of the exhibition the questions from the survey were made available to the audience of the exhibition as well, so that they could ‘touch and feel’ the research on this ‘in the making’.

It would be interesting to use this method of making the audience participants in the process in other exhibitions as well. We could use the results of such participation again for further research on the perceptions of environmental change.

Such natural-social science cooperation in exhibitions on Arctic livelihoods seems to be a fruitful trend, and it’s nice that in Japan they have implemented in their way. Artist Anu Osva did this differently, by drawing geneticists and anthropologists into her art exhibition on human-animal livelihoods with arctic domestic animal breeds. That exhibition was recently on display in the Arktikum in Rovaniemi, in connection with the completion of our ArcArk project.