Foreign, as well as Swedish based mining companies, prospect and exploit – as in drilling – for stones and minerals like never before in Sweden. The country is in at least the local newspapers presented as a Klondike, full of treasures just waiting to be ‘picked up’.

Abandoned and Closed Mines in Sweden – a Neglected Problem?

Parallel to this representation of the Swedish Klondike runs a harsher reality: abandoned and then often toxic leaking mines that are left to the tax payers in Sweden to clean up. This is a known problem also in North America, as the sad history of the giant mine shows, studied by our colleagues Arn Keeling and John Sandlos.

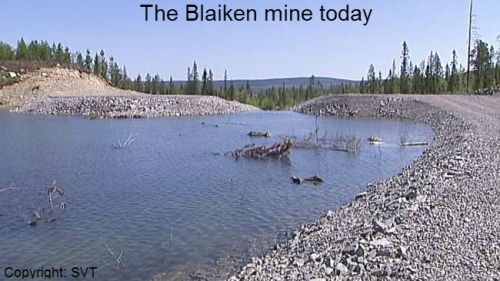

Examples from Sweden are the Blaiken mine and Svärtträsk mine in the county of Västerbotten in the north, (earlier) owned by the now bankrupt ScanMining AB. Blaiken leaks heavy metal to a cost of 1 million SEK a month for clearing the toxic waste. It is estimated that 200 million SEK is needed to clean it up entirely – and the Swedish tax payers are the ones that pay for that. ScanMining that abandoned the Blaiken mine in 2007 had put aside only 3 million SEK for a clean-up of it. Lappland Goldminers bought it with the intention to turn into a zinc mine, even though it was attended as a gold mine when it was started up. Lappland Goldminers attempt did not work out.

Examples from Sweden are the Blaiken mine and Svärtträsk mine in the county of Västerbotten in the north, (earlier) owned by the now bankrupt ScanMining AB. Blaiken leaks heavy metal to a cost of 1 million SEK a month for clearing the toxic waste. It is estimated that 200 million SEK is needed to clean it up entirely – and the Swedish tax payers are the ones that pay for that. ScanMining that abandoned the Blaiken mine in 2007 had put aside only 3 million SEK for a clean-up of it. Lappland Goldminers bought it with the intention to turn into a zinc mine, even though it was attended as a gold mine when it was started up. Lappland Goldminers attempt did not work out.

Blaiken is an open-cast mine, which mean that mining is carried out on the surface, turning it into a ‘hole’ in the ground. After ScanMining went bankrupt, the mine was filled with rain and snow, as well as melting snow in the spring. The clearing ponds could not hold and absorb all the water with the result that it went into the river Juktån.

The same problem occurred at the Svärtträsk mine in the same area as Blaiken owned by the same bankrupt company – the two mines lie just 30 kilometres from each other. At Svärtträsk mine toxic water also leaks into the same river. Attempts are made to reduce toxic flows by adding calcium oxide into the water in the mines (link text in Swedish).

Beside the environmental issues that the former ScanMining’s abandoned mines are struck by, the question is who is responsible for the mines when being abandoned? The Blaiken and Svärtträsk mines are in the hands of the trustee, but it is mentioned on the webpage of the Swedish Parliament that financing the clean-up is the Government’s responsibility, and that are the tax payers in the end (see link above). In Sweden, the mineral tax – the tax mining companies pay to the Swedish state – is today 0,2%, and that is not in any respect sufficient when it comes to legacy costs as in the cases of Blaiken and Svärtträsk that still leak heavy metal. When it comes to ownership of mines, any clean up of abandoned mines would still be Sweden’s national problem, since a bankrupt mine comes with a bankruptcy estate that often is short of money, no matter if the company is foreign or Swedish based.

On the one had, this is a structural problem of mining project lifecycles in general. But on the other hand, there may be a layer of lobbyism and clientilism in those cases that should be addressed too:

Mining Research at Universities and Mining Companies – A Dangerous Liaison? Or a Fruitful One?

Luleå University of Technology (LTU) in the north of Sweden by the coastline of the Gulf of Botnia, has gotten the commission to lead research on mining in the Nordic countries; a commission that is led by professor of geology, Pär Weihed, at LTU. The project is called NordMin, as in “North-Min[ing]” and it is founded by 35 million SEK by Nordic Council of Ministers over a three year period of time. The Council is located in Copenhagen in Denmark.

What type of research can be expected from NordMin and LTU is still to wait for. It must be said that in the article referred to it is written that the project will create a sustainable mineral and mining industry with focus on the chain from exploration/prospecting to the steelworks.

What also should be mentioned is that Weihed is a board member in the exploration company Botnia Exploration AB [Incorp.] that is focusing on exploration for gold and base minerals. The head of Botnia Exploration, Bengt Ljung, said that the company would take “important steps” based on Weihed’s competence (link in Swedish to the statement).

By today – January 2014 – Botnia Exploration holds 3 exploration licenses in the county of Norrbotten, and 11 in the county of Västerbotten, mostly for gold and copper, but also silver, zinc, lead and wolfram, plus one concession to exploit gold in Västerbotten. Wolfram is for instance used in filaments in light bulbs. On the company’s own web-page it says it has 17 exploration permits and one concession license.

The head for SveMin, Per Ahl, stated in an article in LKAB Framtid Luleå [LKAB Future Luleå] in 2013 that Sweden needs more mines (LKAB, Loussavaara-Kirunavaara AB [Incorp.], is the biggest mining company in Sweden and also domestic based). In that same article Weihed proclaimed that the land taken up by exploration licenses – or “concession licenses” as they are called in the Minerals Act – is covering 20.000 hectares, while golf courses take up 28.2000 hectares.

The head for SveMin, Per Ahl, stated in an article in LKAB Framtid Luleå [LKAB Future Luleå] in 2013 that Sweden needs more mines (LKAB, Loussavaara-Kirunavaara AB [Incorp.], is the biggest mining company in Sweden and also domestic based). In that same article Weihed proclaimed that the land taken up by exploration licenses – or “concession licenses” as they are called in the Minerals Act – is covering 20.000 hectares, while golf courses take up 28.2000 hectares.

I will not defy those numbers, but what can happen on a golf course that can be harmful for humans and the environment on the same level as leaking mines? Reducing a heavy industry with everything that comes with that, such as heavy metal leaking mines to the level of harmfulness of recreational sports facilities (golf courses) distorts the public awareness of real mining impacts. Weihed’s proclamation on mining taking up less space than golf courses in Sweden was reproduced in May 13, 2013, on the editorial page in the local newspaper Norrländska Socialdemokraten by Olov Abrahamsson under the title “Svart på vitt om gruvorna” [“Black and White on the Mines”] (link to article in Swedish).

Weihed said in that very same article in LKAB Future Luleå from 2013 that arguments put forth by critics are that foreign mines are allowed to prospect and mine in Sweden, and he fills in that 15 (metal) mines are running in Sweden and 2-3 more are planned, and 8 of them are owned by Swedish based mining companies. So was ScanMining as well, but that did not help much when both the Blaiken and the Svärtträsk mines in Västerbotten, were abandoned after the company went bankrupt, and they still leak toxic waste.

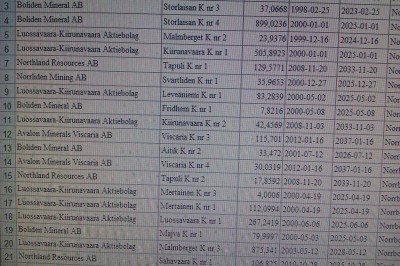

By today – January 2014 -, there are 69 concession licenses for the county of Västerbotten, to a lion part for gold, copper, silver, lead and zinc. In the county of Norrbotten, north of Västerbotten, there are 32 valid concession licenses for mining, mostly for iron, but also for lead, silver, zinc, gold and copper. On top of that there are mines in mid-Sweden. When a company has concession license(s) it means it is running mine(s) or holds permission to open mine(s) according to valid license(s). The greater part of the companies holding concession permits in the two northern counties in Sweden are based domestically. Foreign companies hold around 1/3 of the exploration – as in prospecting – licenses in the two counties.

By today – January 2014 -, there are 69 concession licenses for the county of Västerbotten, to a lion part for gold, copper, silver, lead and zinc. In the county of Norrbotten, north of Västerbotten, there are 32 valid concession licenses for mining, mostly for iron, but also for lead, silver, zinc, gold and copper. On top of that there are mines in mid-Sweden. When a company has concession license(s) it means it is running mine(s) or holds permission to open mine(s) according to valid license(s). The greater part of the companies holding concession permits in the two northern counties in Sweden are based domestically. Foreign companies hold around 1/3 of the exploration – as in prospecting – licenses in the two counties.

But back to the environmental perspective as to mining.

Environmental Issues with Abandoned, and Running Mines

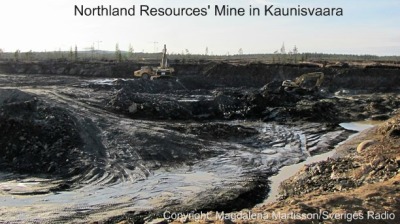

Environmental problems, as Blaiken and Svärtträsk, also got attention at the Kaunisvaara mine, owned by Northland Resources, in Pajala, close by the Finnish border in the north of Sweden. Besides being on the verge of bankruptcy, a situation that was saved when the mining company LKAB stepped in and bought a lot of shares, is the mine’s clearing ponds containing more water than they are built and estimated for, with the result that toxic substances do not fall to the bottom, but are floating up to the surface and leaks out instead. That very same problem also became a national scandal in Finland’s north in the Talvivaara mine, were the Finnish state now had to take over shares of the company to prevent it from going bankrupt.  A high level of toxic waste has been recorded in the small rivers around Kaunisvaara, rivers that are connected to the bigger Mounio River on the border between Finland and Sweden. The Mounio River runs into the Gulf of Botnia; a gulf severely struck by high rates of toxic substances in the seal population as well as the Baltic small herring population. The (Baltic) small herring in the Gulf of Botnia is so full of the toxic substance dioxin, that it would not be allowed to be sold in stores, if it not had gotten a permanent exception from the EU parliament because it is the fish being used for the Swedish traditional dish “surströmming”, fermented Baltic herring that is (Swedish link to the EU exception).

A high level of toxic waste has been recorded in the small rivers around Kaunisvaara, rivers that are connected to the bigger Mounio River on the border between Finland and Sweden. The Mounio River runs into the Gulf of Botnia; a gulf severely struck by high rates of toxic substances in the seal population as well as the Baltic small herring population. The (Baltic) small herring in the Gulf of Botnia is so full of the toxic substance dioxin, that it would not be allowed to be sold in stores, if it not had gotten a permanent exception from the EU parliament because it is the fish being used for the Swedish traditional dish “surströmming”, fermented Baltic herring that is (Swedish link to the EU exception).

There is of course research being done on so called “Green Mining”. And a professor in environmental geology in Sweden says that a fund is necessary for the mining industry in Sweden, in order for the country to have enough money for tasks such as cleaning up abandoned mines.

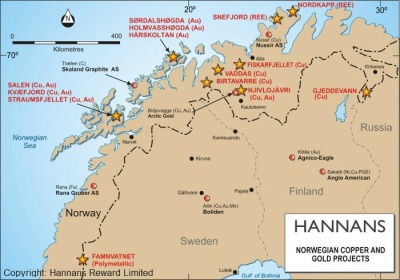

‘Detoxing’ mines is not the only issue at hand. The locations are also relevant, as a newly arisen discussion shows on Australian Hannan Rewards Ltd exploration/prospecting license in the vicinity of the high mountain of Kebnekaise in the north of Sweden via its subsidiary company Kiruna Iron AB.

Mines at Kebnekaise? – the Highest Mountain Top in Sweden

The title can seem populist, but nonetheless the question of the actual location of planned mines is an important issue. Many mines in Sweden, at least in the north of the country, are located on reindeer herding grounds. The latest prospecting licenses given by the Mining Inspectorate of Sweden are given for localities just a few 10 kilometres from Kebnekaise, the highest mountain top in Sweden and a well visited tourist destination.

The exploration work in the vicinity of Nikkaluokta, the gate to Kebnekaise, is carried out by Hannans Rewards Ltd and its subsidiary company Kiruna Irons. On the Australian webpage of Hannans Rewards Ltd, the gold and copper project Pahtohavare is presented as “a high grade copper-gold project located close to modern infrastructure and first class mining services, in a low sovereign, mining friendly country”. So Sweden is by Hannan Reward portrayed as a development country as to mining. The other mining project the company has is mining for iron in Kiruna, and the head of the company declares: ”Hannan will allocate the majority of its future funding towards developing the Kiruna Iron Project” .

Hannan has also 10 mining projects in Finnmark, Troms and Nordland in the north of Norway, mostly for copper and gold. Scandinavian Resources Ltd, and its subsidiary companies Scandinavian Resources AB and Kiruna Iron AB, do all belong to Hannan Reward Ltd.

Sources (where there are no links in the text):

Gröning, Lotta, ”Dumheten får förhoppningsvis konsekvenser”, Expressen, December 28, 2013.

Olovsson, Ronny, ”Gruvforskningen i Norden samordnas i Luleå, LKAB Framtid Luleå, no. 1, 2013: 5.

-, ”Kritikerna har fel: Vi behöver fler gruvor”, LKAB Framtid Luleå, no. 1, 2013: 5.

Further reading:

Müller, Arne, Smutsiga miljarder: den svenska gruvboomens baksida, 2013. [Dirty milliards: The Backside of the Swedish Mining Boom] ONLY IN SWEDISH!

Sweden a developing country? Hmm, I wonder what is meant when that company describes Sweden as a “low sovereign-risk country”. Is this hinting at the situation in South-Sudan, are mining companies afraid of political unrest where they work? If so, then yes they are right, there doesn’t seem to be a danger of this anywhere in the Arctic, right?

In general, this reimagining of the Arctic as a frontier where the resources just wait to be “picked up” is a backwards move to 30 years ago, when the indigenous movement just started to lobby for the idea of the Arctic as a homeland. We talked about this recently with Mark Nuttall in Rovaniemi after his talk on Greenland, and he coined this idea of the “refrontierisation” of the Arctic. Where did these decades of Arctic People’s activism go? This is rather worrying!

Maybe “developed country for mining” is even more proper(?) in connection to the fact that a company describes Sweden as a “low sovereign-risk country”. I do too agree upon that there is a reimagining of the Arctic, and the North, as a frontier. Then the areas behind the frontier can be looked upon as well as treated as ’empty’ of people, meaning, history – nothing but an ’empty space’ lying to be filled with extraction of natural resources and the services that follows with that. I mean that that show that the situation also is a question of power of discourse in a foucaulian sense, which raises questions such as; who is creating what type of discourses and what power can they and do they exert? Many mining companies seem to use one and the same discourse that put them in a leading power position because it attracts politicians, governments and even countries on a national level – many countries that have areas with high unemployment such as northern Sweden and northern Finland where extractive industries are seen as ‘a Saviour’. A power that is exerted out of a discourse that has become a canon. As for now. The discourse is filled with contradictions such as unemployment-employment, no public service-extended public service, move out-move in, no future-future, where the extractive industries, like mining companies in Sweden, are said and appointed to stand for everything on the plus-side in the contradictory states.